Policy into Practice – workshop on 16th August

Run in Partnership with York Explore

Our aim with this event was to look seriously at key policies held by the council which reflect the principles and aspirations of local people and their representatives. We are a One Planet city which implies a broad set of principles; there is a commitment to a transport hierarchy that puts pedestrians, people with mobility problems and cyclists at the top; we are a Human Rights City and also a UNESCO Creative City. We were interested in using this workshop to explore what this might mean for York Central.

But how? We decided that the key indicator was a simple question:- “if you woke up on York Central in 15 years time, how would you know this policy had been fully realised? What would you be doing? Who would be there? What could you see? What could you hear? How would it feel?”

Opening presentations were given, and discussions around four tables were facilitated by:-

Chris Bailey speaking on UNESCO Creative Cities

Liz Lockey speaking about York: Human Rights City

Mark Alty speaking on One Planet York

Phil Bixby standing in for the CoYC transport team and outlining York’s agreed transport hierarchy.

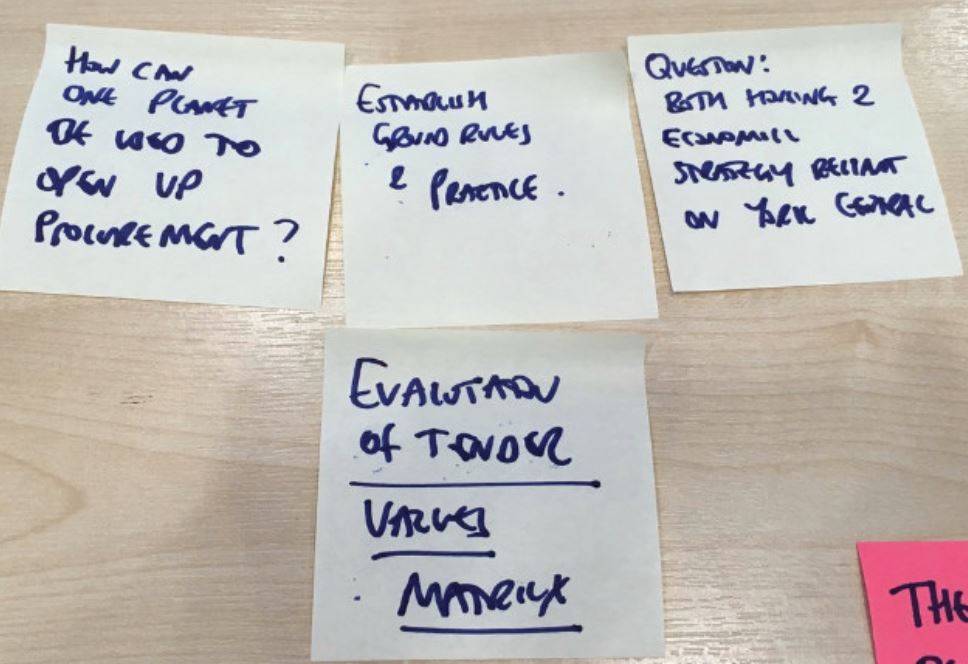

Discussion was lively, and Post-Its from the discussions can be found, as with all our Post-It-based input, tagged and sorted on our Flickr site.

Following the event, Chris Bailey wrote a short but thoughtful piece which references the UNESCO designation but notes that human rights should be at the heart of thinking about everyone’s life and creativity:-

Just ‘living life’

Looking back at 2014, when we won the title of York UNESCO City of Media Arts, I must admit many of us wondered how this relates to our beautiful, historic city.

Part of it is that we got off to a false start. Like all councils, York thought mostly in terms of priorities, things they have to do (inevitably with too little money!) to avoid doing harm or to fulfil a Government inspired target. No wonder they always looked for the ‘quick wins’. The connection to the way people actually live their lives often seemed remote, even when the policy was something vital, like providing good housing. The ‘services’ on offer, we lazily thought, were meant for someone else, someone less fortunate than us. The problem is that, at some point, that ‘someone’ actually is us. Why should what we want for others, be different from what we want for ourselves, or our children?

A conversation back in 2018 put us on the right track. We don’t ask to have things go wrong in our lives but we live with the consequences of disabling illness or injury, or worsening conditions. If you have to use an electric scooter to get about then decisions about urban design can easily cut off your potential to be parents, productive workers, or valued friends. This is bad for our wellbeing, and for the community as a whole. The technology that gives the benefit of shopping online also gives us the challenge of streets clogged with delivery vehicles, and hours trapped at home awaiting a vital delivery. Technology must be transparent in operation and accountable in its application.

We realised then that policies should always start from our potential as human beings, as people and as citizens. A truly Creative City seeks to develop the talent in everyone, and to provide space for participation. It also ensures that our leisure and cultural organisations are responsive to the wishes of the community and reflect their identity and traditions.

And in the spirit of Paul Osborne’s wonderful bit of future thinking for the 2018 Festival of Ideas, Phil Bixby condensed discussion at his table into a brief description of life on a future York Central with a transport hierarchy:-

The joy of a blank sheet

We’ve often made excuses for poor transport in York – the historic city, the narrow roads. But York Central was a clean sheet – a chance to design a piece of city from scratch. It cried out for radical ideas. Why didn’t Network Rail take a lead in proposing rail-based transport? It’s a mystery. We needed ideas which would appeal to the next generation – where you get the kids excited and they pass it on to their parents.

Behaviour change

We needed to break down the barriers between modes of transport – it’s not about “being a cyclist” or “being a driver”. I have a car, but I don’t use it in town, for all sorts of reasons. Some of the radical ideas make me smile – when deliveries turn up by pedal power for example. And people have changed – a friend now does the school run with her kid in a cargo bike. He thought he’d be a local celebrity but in fact there are so many of them now he just waves to other kids in cargo bikes!

That process of change was interesting – it took a measure of nastiness to stop “those journeys which weren’t necessary”. The car to the corner shop, the school run because walking meant leaving ten minutes earlier. Congestion charging was considered but rejected as being unfair to the poor. In the end it came down to making things visible – they fitted a big interactive sign on all the main roads into York showing pollution levels and pictures like on fag packets – clag pouring out or arteries and stuff – and it worked. There was talk about pumping some sort of chemical into the air which made the pollution visible – instant smog – but in the end people got the message before it happened.

Walking and cycling

I can walk to the station along good, car-free routes – not just back alleys but main walking routes – which connect up and make a permeable area. The footways are level and wide, so older people and wheelchair users actually use them, and in winter the snow is cleared on the footways (and cycleways) before the roads.

Junctions are designed for pedestrians and cyclists – all traffic lights have a cycle-only slot at the start of each light change which gives cyclists time to leave the junction (not just a couple of seconds head start). Traffic lights give equal time to pedestrians too – I recall a few years back counting 21 pedestrians waiting to cross a junction, and there were fewer occupants in the cars which the lights let through. How was that a hierarchy? There are so many more cyclists now, and all sort of different bikes – real signs of change.

Public Transport

I can get a bus easily too – with genuinely useful connections across the city – not just the radial routes. They’re reliable because there are fewer cars clogging the roads, and many more bus-only routes. They’re cheaper too, which works because they’re well used. They work well – they once again have space for luggage, and are comfortable, like coaches. They have enough time on their routes to actually let older people sit down rather than tearing off as soon as the last customer is past the ticket machine.

The other big difference is that they’re in public ownership, so social value is built into all contracts, and drivers are properly paid (lives depend on them, after all).

A transport hierarchy was never just about making everything easier, but about making choices. Until driving was made less convenient, sustainable transport never stood a chance, but now it’s the way we all get about, most of the time. And when you do need the car – you may have to go further but the roads are so empty!