Housing Histories, Housing Futures: What can we learn from looking back at York’s so called ‘slum clearances’?

Saturday 24 March, 1.30pm-3pm

York Explore Libraries and Archives

The Housing Histories, Housing Futures event in collaboration with York Past and Present and York Explore Libraries and Archives was based on work done in 2015 and 2016 on the histories of housing in York and especially looking at the Hungate inspections and clearances.

We opened with Introduction to York Central. A key focus for York Central is homes, with both the Council and Homes England as members of the York Central Partnership which have a specific policy interest in house building. Throughout the session – as we looked back – we kept returning to this question: what principles can we draw out for how government and communities should work together?

We looked back two key moments in the Hungate clearance. Catherine Sotheran had explored the 1911 Census, revealing a wide diversity of occupations not quite what might be expected from a ‘slum’:

The majority of adults are in work, the most common occupations being in the Chocolate industries, general labouring jobs, laundry and other domestic type jobs, trades like painters, joiners, wheelwrights etc. but also a few more skilled jobs like a hairdresser, midwife, auctioneer, book binder, dressmaker, druggist and antique dealer. There also seemed to be quite a few people involved with fish, either as dealers or fish fryers.

We then went on to look at some examples of health inspections which were used to underpin mandatory improves, leading even to the authorities just making changes and sending a bill through. Even, as Catherine found out, they didn’t know exactly who owned the house in question!

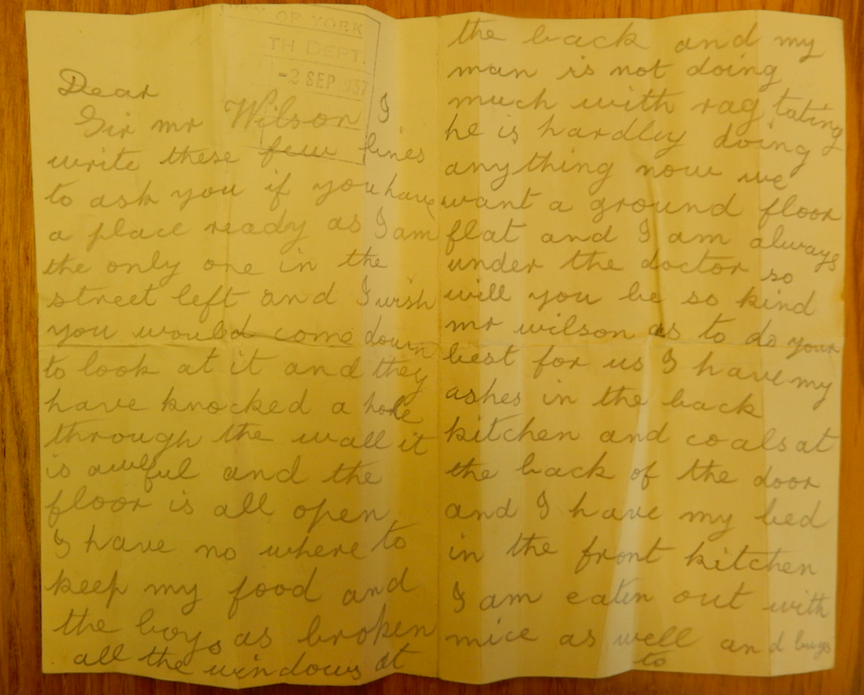

In the 1930s the improvements had led to being clearances as people were moved to new housing in Tang Hall and Clifton. Here were found some personal stories creeping soon, a woman who was forced into an institution, a story found by Sue Hogarth, and as you can read below, a letter from a man who was the last on their street.

Reflecting on how we could see the authorities and people interacting – often individuals seemed very much an afterthought in the 1930s – we skipped forward to the 1970s where a different mood was in evidence.

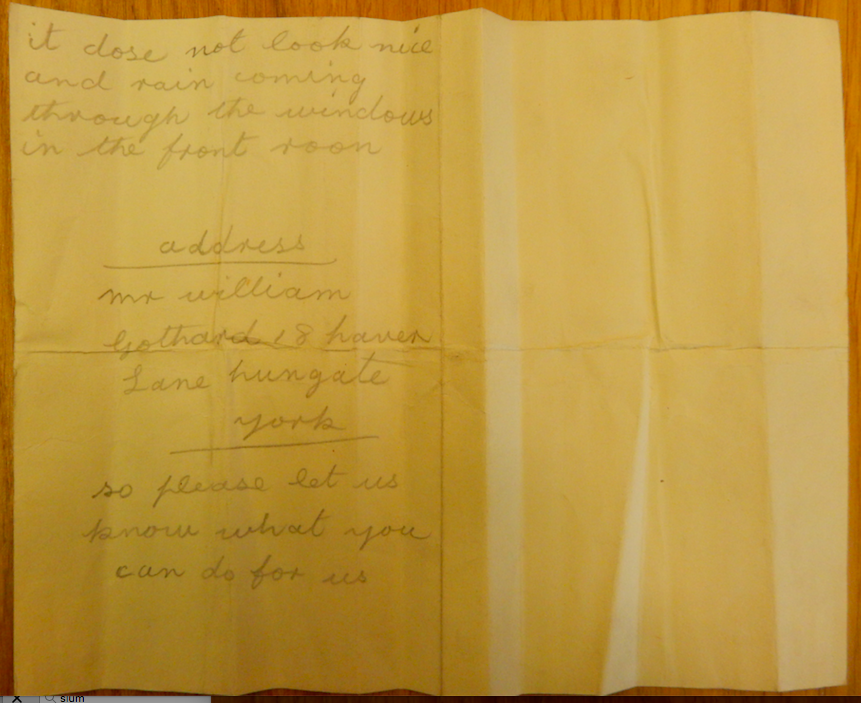

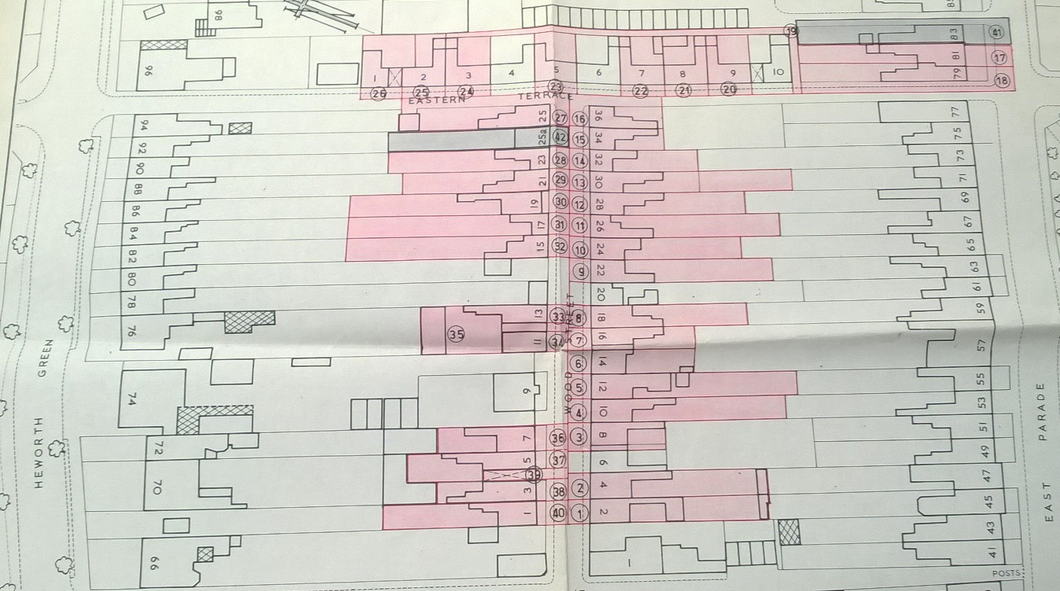

In our 2015 project Carmen Byrne had found a series of correspondence between a woman in street due to be demolished in Layerthorpe, we went back and read parts of her blog written at the time:

One tenant from Eastern Parade wrote to the Public Health Inspector in January 1973 requesting further information as she’d “held back a week’s holiday which must be taken before the end of the financial year”, so she was “naturally anxious to know if we are likely to move in the near future”. The resident’s uncertainty stemmed from having no news since she visited the Inspector’s office around one year earlier and her concern about a series of “cleaning and replacement jobs which must be done if we are going to be here longer”. This would suggest that there was little transparency or communication with the residents during the process, and again reinforces the lack of ongoing investment into properties already resigned to demolition.

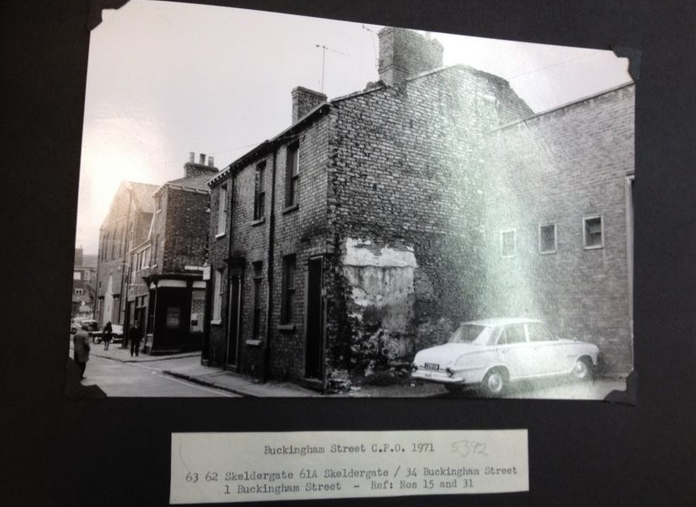

We then looked briefly at the Bishophill Action Group and there work to save streets which were planned to be demolished to make way for multistorey car park. This activism evoked quite a different relationship with the local government that was visible earlier, as one member of the Bishophill Action Group group put it in a press article: ‘if the corporation had wanted the street, they could have got it a lot more easily than by calling it a slum. This has put our backs up. We feel they are using underhand methods.’ 20th September 1972

We then ended by reflecting on these histories… what principles can we draw out for how government and communities should work together?

Changing expectations of involvement

We noted that in the two major cases of 1911s and 1930s and the the 1970s, that between this period people clearly had come to expect to have more control over their lives.

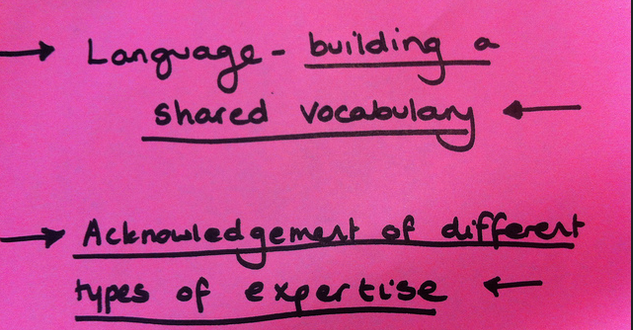

Problem of jargon – and the need for shared language

This lead to a lot of discussion about how to build shared language and respect the expertise that comes from living somewhere, not just professional experitise/

Community is fundamental not just brick and mortar: ‘They treated housing like a problem to be fixed and ignored the problems they created in terms of lack of community’

An interesting insight from the discussion was the way on which the authorities treated housing as a problem that need simply to be fixed with improvements or new housing. This had the effect of ignoring all the other aspects of ‘home’, ‘belonging’ and ‘community’.

Need for government intervention in the market, but with involvement of those affected

There was however a strong feeling that govenrment is not in itself bad – nd that we needed interveiton from the public bodies involed in York Central. But with greater involvement from local people.

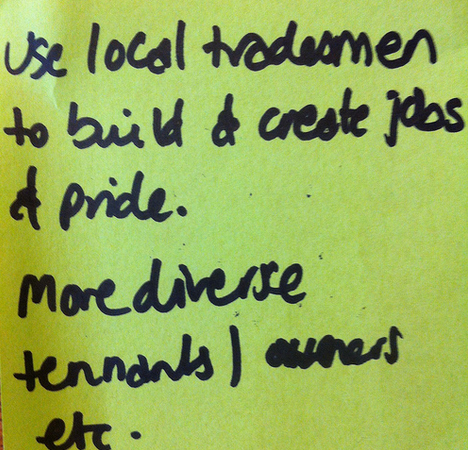

Community involvement in designing and building?

This lead to a discussion about how communities could be actively invovled in design and build of housing.

Slum then, affordable now?

We concluded with a very interesting discussion – building on the discussion above about language. It would be rare to hear the word slum now – it is considered a negative and pejorative word as the Bishophill Action Group pointed out above. Yet, it was asked, is is possible that affordable does similar work today in that it categorising certain groups and seperating them off from others?