Week 4 of the Festival of York Central was focused on ‘movement’, asking how people wanted to get to, across and around York Central. We’ve gathered information through social media and through a series of events:-

- Beyond Flying Cars – sustainable transport on York Central – joint York Environment Forum / York Bus Forum open event

- Getting Out More – family drop in workshops leading to production of a zine

- York Central Transport & Access with Professor Tony May

- Connecting York Central & Holgate – walk with local residents re proposed southern pedestrian/cycle access routes

- Out and About workshop sessions with pupils of St.Barnabas and Poppleton Road schools

- What Makes a Good Cycle Route – guided ride and workshop with York Cycle Campaign

- Pulling together the Week’s Conversations – public workshop (with The Life Sized City film show)

We have also drawn upon movement-related discussions during previous weeks – for example on issues of legibility in shared space (from our Open Spaces discussions) and the role of transport in urban development (from the David Rudlin workshops). In addition, tagging of comments from previous events has allowed us to put responses from the week’s events in a broader context of overall comment, questions, etc.

Here are the main issues and comments:-

Some key principles:

York Central cannot be seen in isolation. One of the recurring themes of discussions on movement was integration – transport modes and routes need to connect to make them useful. A truly high quality transport network on York Central needs to integrate with a truly high quality transport network across the city. So:-

- People felt that York Central should set an example of innovative, forward-thinking sustainable transport and…

- York Central should be an opportunity to leverage change across the city and bring forward broader innovation – for example new networks (Very Light Rail, continuing through the city and onwards to Heslington / Elvington) and processes (freight trans-shipment for local deliveries, with small electric vehicles / cycle couriers).

- We should design for behaviour patterns that we want in future rather than just to work with current patterns (for example prioritising active travel).

- Prof Tony May set out the hierarchy of priorities within the draft Local Plan and stated clearly that design of movement infrastructure within York Central should reflect this, with clear and convenient walking/cycling routes occupying space best suited to them, and vehicular routes elsewhere. This was widely supported.

- There should be better separation between vehicular routes and cycling routes – these should be truly segregated (not immediately adjacent) and walking/cycling routes should always have priority.

The need was identified for good-quality information to steer future decision-making. For example:-

- What will changes in overall age of population mean for transport demand? Will there be more people with mobility issues? More mobility scooters?

- Can we obtain information about what journeys people want to make (not simply traffic counts on roads – information about “why”) so we can consider and design for end-to-end journeys?

- What is the basis for decision-making on car use/ownership? Is this simply the status quo (“most people have cars, so we design residential areas for cars since moving away from this would result in resistance”) or is this on the basis of alternative possibilities (“there must be lots of people for whom a car-free neighbourhood this close to the centre would command higher house prices”).

Reducing movement by reducing zoning

Can we reduce the need for people to move around by the way we plan the development?

“We thought the future would be working from home and having meetings via Skype; do we no longer believe that we’ll all be working from home?” “It’s not become an either/or, people are not using it as a replacement”.

There seem to be movement implications from this as follows:-

- Working from home will still require movement but this can be largely walking/cycling

- Small/medium businesses (for example creative industries) often involve “clustering” where good local connections (again walking/cycling) are important.

Public transport and the rest of York: Ease of use and Integration

- Seamless connections with a wider network are needed to allow necessary longer journeys – simply getting to the city centre is inadequate if onward connections aren’t easy and fast.

- This needs to consider both the radial routes and movement between them – York is poor for this.

- Ease of use is essential – contactless payments on all transport modes, and operating times / pricing models which suit users rather than just operators (current Park & Ride arrangements were frequently criticised).

- All of which points to a requirement for some over-arching strategy and an appropriate body to administer it, an equivalent to Transport for London – Transport for York – was mooted.

Pedestrian and cycle movement

Key points were that:-

- There is less distinction between cyclists and pedestrians than there was between people wanting to use the fastest direct route and those wanting to linger

- Shared space can work okay with pedestrians and cyclists – subject to enough space and the point above, but not where motor vehicles are also included.

- Where there are routes intended for direct, rapid use, these need clear, legible marking (using different colour/texture).

Cars on York Central: Low car development and no through traffic

A crucial choice is whether there is through traffic across York Central. One comment was “If you allow through traffic, this is where all ideas of being radical evaporate”.

Many people noted that there seemed to be an assumption that “restricting car use/ownership” was seen as problematic and would decrease the appeal of living/working on York Central, but that this was open to challenge. There were many suggestions that a car-free neighbourhood would be very popular and would command premium prices. “People will have a choice – no-one is being forced to live here”.

Prof Tony May set out a proposal for York Central based upon the Freiburg Vauban development – allowing car access but with centralised parking, creating Play Streets and safe walking/cycling routes. It was noted that this would require consideration (for example Respark areas to prevent “overspill”) beyond the site. This side-steps the “ban cars” challenge by allowing ownership but passing on real costs and making alternative modes more attractive.

Prof May’s ideas envisaged centralised parking at the north-west end of the site, close to the access from Water End. Bringing cars deep onto the site to multi-storey car parking adjacent to the station was felt to be a backwards step, which would greatly reduce safety within the development. Parking for service use (tradespeople etc) was discussed and it was felt bookable spaces could be provided. Local deliveries could be to service points, combined with public transport stops or parking areas.

Marble Arch / Leeman Road tunnel: How to avoid traffic cutting up the New Square

People stated that the main access to the site (and NRM) from the city needed to reflect the City’s transport priorities – it should be a good route for those walking / cycling etc. Its poor visual appeal was noted and the question was asked “what would it take to turn it into the gateway to a major museum?”

The impact of through traffic on the new square was frequently mentioned. Both two-way through traffic and light-controlled alternate traffic (Option 2 on the Marble Arch board) were thought likely to lead to queuing traffic in what has been described as a pedestrian civic space, which should be avoided. Traffic was furthermore seen as a potential barrier between the NRM and the station / city centre.

National Railway Museum through access: A creative opportunity to celebrate movement

There was almost complete opposition to the closure of Leeman Road to pedestrians/cyclists outside NRM opening hours. It was noted that modelling suggests it would take people on foot 1.5 to 3.15 minutes longer when the museum was closed. There were comments like ‘it’s not about how much longer it will take’, ‘it’s the psychological factor of feeling cut off and that the museum is blocking you’.

More positively, there were comments like “I don’t think it’s about the time saved or not, it’s about the experience and qualities of being able to walk and cycle through the museum”. There were repeated requests for a more creative solution which celebrated movement (“it’s bizarre that a museum of movement would cut off movement”) and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam was cited as a good example of what could be possible, with new opportunities for the public to see exhibits while maintaining out-of-hours security. Creative possibilities were identified around rotating doors or a turntable in the link building – “like the Gateshead Millennium bridge – people would come to watch it open!” and “the shadowy trains in the closed museum are far more atmospheric than when it’s open”.

Connections to existing communities

There has been an assumption that York Central should connect to surrounding communities but this was noted to have challenges:-

- The simple fact that people who are used to being disconnected from public movement may be suspicious of change

- Issues to do with alcohol and antisocial behaviour – new bars in York central leading to hen parties making noisy progress through surrounding communities

- Places which offer security (for example Holgate Community Garden) becoming open and routes for (pedestrian/cycle) through-traffic.

There was a broad point made that the development needs to provide positive benefits for existing nearby residents and needs to clearly spell these out. “You compromise. Part of this is “I’m not going to get that bit that I really want but I’m going to get that other bit instead”. There has to be a quid pro quo”. This applies to movement as well as other facilities.

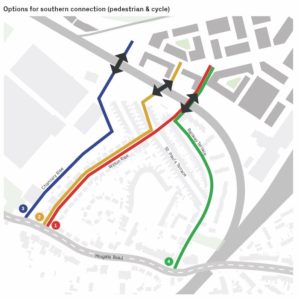

Discussion of the proposed southern connection is covered in a separate document.